In a war that claimed over 50 million lives, a single incident that lead to 173 deaths can seem like just a drop in the ocean, but the tragedy at Bethnal Green Tube Station still stands out as one of the most devastating incidents in wartime London. What isolates this incident is that, in reality, it was entirely preventable.

In 1936 it was decided that the Central Line would be extended to run beyond Liverpool Street to Stratford. As building the new line was halted during the war the tunnels and stations were left empty, and subsequently East Londons began using Bethnal Green as an air raid shelter, rather than the uncomfortable Anderson and Morisson Shelters provided by the Home Office.

The shelter at Bethnal Green was massive, fitted out with 5,000 bunks, with room for 2,000 more, and complete with library, musicians and entertainers. Londoners whiled away many hours here in the subterranean community while bombs rained down above.

Bethnal Green Station today

On 3rd March 1943 however disaster struck. Following heavy bombing of Berlin London was preparing for retaliation, so when the alarm sounded locals rushed for shelter as usual. The steps down to the shelter were dark, only 1 light illuminated them, there was no markings on the side, or central hand rail, and as was customary London was in Blackout conditions. As East-Enders began making their way down the stairs a lady carrying a baby and a roll of bedding tripped and fell on the stairs, an elderly gentleman tripped over her, and thus began a devastating cascade of human dominoes. In the darkness nobody knew of the danger ahead, and Londoners kept hurrying down the stairs. The arrivals of two buses full of people looking for refuge only accelerated the disaster. A few miles down the road, in Victoria Park new bombs were undergoing secret testing, giving the impression of a German air-raid and only increasing the crushing panic.

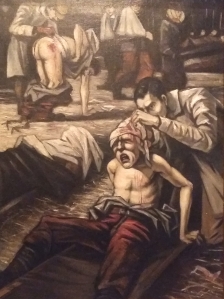

In a matter of minutes 173 people were dead, including 62 children. A further 90 were injured. The bodies pulled from the staircase were purple and bruised beyond recognition. One child was only identified by a cobbler, who remembered adding a nail to her shoe the day before!

On the 3rd March 1943 not one German bomb fell on London, in fact, not even one enemy aircraft was spotted, there was no danger to London, and yet there had been huge civilian casualties! Upon hearing of the disaster Churchill ordered that it be covered up. Survivors and witnesses were told of the importance of their silence, and some never spoke of it in their life times. Churchill believed that news of the Bethnal Green disaster would lead to a huge drop in morale and public spirit, and thus a cover-up was initiated.

It wasn’t until 2 years later that the Home Office released their official reports, along with the autopsy reports from the Police Surgeon. Even to this day no memorial stands to the victims, save a small plaque, which frequently goes unnoticed. The Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust has been fundraising to install a memorial by the tube station, of an inverted staircase. Designed by Harry Paticas, the memorial was entered in to the Royal Academy of Art’s prestigious Summer Exhibition in 2012. Whilst more funds are still needed to complete the memorial, the Trust are still highly active, and every year on 3rd March, a memorial service is held.

Over 70 years later, it is astounding that the deaths were covered up so easily, and that the tragedy is still so unknown! Family members of those killed were given only a pittance as compensation (around £950 for adults and £250 for children), and many took the psychological scars to their graves. A list of those who were injured, or died can be found on the Stairway to Heaven website.

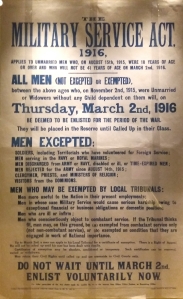

In 1916, for the first time in the history of the British Army, conscription was introduced. It would last until 1920, and called all men aged 16-41 to join up and fight during the First World War.

In 1916, for the first time in the history of the British Army, conscription was introduced. It would last until 1920, and called all men aged 16-41 to join up and fight during the First World War.