On a cold drizzly Sunday afternoon in York, when we’d exhausted all the coffee shops, and seen all the ‘must see’ tourist attractions we decided to check out an English Heritage site, just outside York. It definitely should have been higher on our priority list!!

Hidden away, surrounded by blocks of flats lies the entrance to the York Cold War Bunker, only visitable by guided tour. As luck had it the next tour was in 5 minutes. Our tour guide, Anna, was clearly incredibly passionate about the Cold War, and her enthusiasm was infectious! We were the only two people on the tour, and she gave us plenty of scope and opportunity to ask questions as we went round.

This Cold War Bunker was the operational HQ for the Yorkshire division of the Royal Observer Corps (ROC), a civilian branch of the RAF. Originally formed during WWII to identify enemy planes, the group was stood down at the end of the war, before being reformed during the Cold War to take readings of any nuclear bombs that fell. From the base they could take readings of radiation levels, try and identify where the bomb fell, and what size it was.

1st step on the tour was to watch a short video highlighting some of the history of the Cold War, and the provisions the British Government had in the eventuality the war went nuclear. Having visited a couple of Cold War bunkers in Berlin earlier this year, the difference was stark. The German Government made civilian bunkers, and promised the people they all had a place to go. In fact their bunkers could only hold about 1% of the population, and some took a week to be prepared and made operational. The British Government had a different idea. They showed people how to make their own bunkers at home, to stock with them with food, paint windows white and reinforce them with sandbags. With the ever increasing strength of nuclear bombs being developed these ‘bunkers’ or safe rooms would have been just as futile.

The York Cold War bunker could keep 60 people alive for up to 30 days. Over the course of the 30 days all the inhabitants would work in 3 groups of 20 on an 8 hour rota. 20 people would be working in the operations rooms, 20 people would be in the canteen relaxing, and 20 people would be sleeping in the dorms on a delightful ‘hot bed’ system. When 30 days was over they would all have to leave the bunker and go into what was left of the world above them.

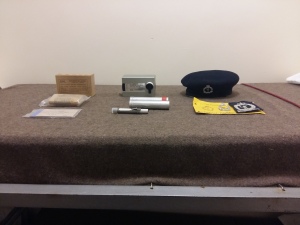

Thankfully the bunker was never needed during the war, although the ROS often ran 48 hour training weekends. So many volunteers couldn’t stand the sleeping conditions even for this fraction of time, and went without sleep, instead of braving the bunk-beds. The photo left shows some of the personal effects of an ROS member on one of the thin beds. No reminders of home, family or friends were permitted in the bunker, as the government feared it would cause psychological damage, not knowing whether friends or family were alive.

Thankfully the bunker was never needed during the war, although the ROS often ran 48 hour training weekends. So many volunteers couldn’t stand the sleeping conditions even for this fraction of time, and went without sleep, instead of braving the bunk-beds. The photo left shows some of the personal effects of an ROS member on one of the thin beds. No reminders of home, family or friends were permitted in the bunker, as the government feared it would cause psychological damage, not knowing whether friends or family were alive.

Those posted in the operations room would have a busy 8 hours ahead. They had to collate all the data gathered from other ROC groups around Yorkshire, and combine it with their own data. The equipment pictured right was used by all branches of the ROC. The long cylindrical piece of equipment hanging from the ceiling was a form of gieger counter which would measure radiation levels below ground.

Those posted in the operations room would have a busy 8 hours ahead. They had to collate all the data gathered from other ROC groups around Yorkshire, and combine it with their own data. The equipment pictured right was used by all branches of the ROC. The long cylindrical piece of equipment hanging from the ceiling was a form of gieger counter which would measure radiation levels below ground.

The white cylindrical box was installed on the roof of the bunker, and was used to identify the location of the bomb. Holes had been drilled into the metal container, which housed photosensitive paper.

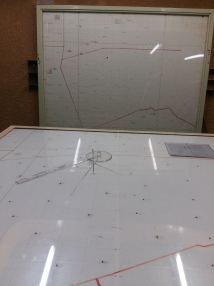

When a bomb dropped, the initial brilliant flash of light  would be registered by a dark dot forming on the gridded paper. The data from all the boxes across Yorkshire would be collated, and using a technique similar to triangulation, the location could be estimated using a map (pictured below). In order to collect the paper from the box , a member of the corps would have to venture outside the safety of the bunker. To ‘protect’ him from the deadly radiation the Government issued a cotton boiler suit, more as a psychological protection than a physical one.

would be registered by a dark dot forming on the gridded paper. The data from all the boxes across Yorkshire would be collated, and using a technique similar to triangulation, the location could be estimated using a map (pictured below). In order to collect the paper from the box , a member of the corps would have to venture outside the safety of the bunker. To ‘protect’ him from the deadly radiation the Government issued a cotton boiler suit, more as a psychological protection than a physical one.

As the war progressed more sophisticated technology was developed in computing. A.W.D.R.E.Y. (right) essentially did the same job as the volunteers in terms of locating a bomb’s epicentre. She did have a couple of flaws, including thinking every episode of lightening, or firework was a nuclear bomb. For this reason volunteers continued to perform manual analysis of the data.

As the war progressed more sophisticated technology was developed in computing. A.W.D.R.E.Y. (right) essentially did the same job as the volunteers in terms of locating a bomb’s epicentre. She did have a couple of flaws, including thinking every episode of lightening, or firework was a nuclear bomb. For this reason volunteers continued to perform manual analysis of the data.

Volunteers would collect information from other branches. Sitting in rows like this they would write all incoming data onto the screens, which could be flipped around, so those working below could analyse the information.

Those working in the room below would work to collate information and locations of bombs over a wider area. Working on huge maps of the North of the UK they would also communicate their findings to other branches and the government.

Those working in the room below would work to collate information and locations of bombs over a wider area. Working on huge maps of the North of the UK they would also communicate their findings to other branches and the government.

Cold War bunkers can be either bomb proof, or blast proof. Bomb proof shelters can withstand bombs falling directly onto them, or in the area closely surrounding them. Blast proof shelters can only withstand ‘near-misses’. Having been designed in 1955, before the mass up-scaling of nuclear bomb strength, the York bunker could only survive a ‘near-miss’ 8 miles away, from a small bomb. If anything fell closer the shelter would have been flattened, or incinerated.

In the wake of recent political events (damn you Trump) the likelihood of a hot war seems to be ever increasing. Unfortunately this bunker would provide very little protection in the event of a nuclear bomb falling on Britain. The increasing payload of modern nuclear bombs makes survival chance much smaller, and if the bunker wasn’t flattened the vital equipment needed to sustain life has probably been decommissioned now. The air-conditioning unit contains materials now banned by the EU, batteries no longer work, and air filtration systems have never been tested. If the government does find itself in a situation where nuclear bunkers become necessary, chances are they’ll just make new ones. That seems to be the 21st century way!

In the wake of recent political events (damn you Trump) the likelihood of a hot war seems to be ever increasing. Unfortunately this bunker would provide very little protection in the event of a nuclear bomb falling on Britain. The increasing payload of modern nuclear bombs makes survival chance much smaller, and if the bunker wasn’t flattened the vital equipment needed to sustain life has probably been decommissioned now. The air-conditioning unit contains materials now banned by the EU, batteries no longer work, and air filtration systems have never been tested. If the government does find itself in a situation where nuclear bunkers become necessary, chances are they’ll just make new ones. That seems to be the 21st century way!

When English Heritage decided to save York Cold War Bunker, they found it in a state of disrepair. The sewage outflow pump had been turned off, and so was no longer pushing water out. Without the positive pressure, water started flowing back in, leaving the bunker flooded, and the task of restoring it that much harder.

Just over a decade ago the bunker opened its doors to the public. Over the past ten years many members of the ROC stationed there have returned and shared their memories of the bunker. Many found love there, some found new extra-marital love there, and one volunteer even went into labour!

The bunker is open by guided tour to the public every weekend, and can be visited during the week for schools or groups. Entry is free for English Heritage members and costs £7.00/£6.30 for adults or £4.20 for children. The price includes an hour long tour, and there are 6 tours a day.

This was one of the best English Heritage sites I’ve visited so far, and I’d highly recommend it! Our tour guide, Anna, brought the whole place to life and was clearly incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about both the bunker and the Cold War, she really made the trip! Thank you Anna!!

Very interesting (and somewhat scary)! It’s cool to be able to see similarities, and a few differences, in American and English Cold War-era bunkers and bomb shelters. Here, there seems to be more practical use, as opposed to American bomb shelters that were designed to appease people afraid of a hot war breaking out. I’m glad it’s a part part of English heritage. Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. I saw a different angle of this about 13 years ago: an abandoned intermediate-range nuclear ballistic missile installation in Lithuania . . . in the midst of a national park. I do not know if it was targeted on York, though it would quite a coincidence if it had been!. Even a more unpleasant place with cramped quarters (resembling a submarine), and suffered damage when the USSR pulled out, taking the missile with them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: People Power: Fighting for Peace @ The Imperial War Museum | That History Girl